While technology (warming trays, thermostats, timers, X10, Shabbat settings on refrigerators and ovens) have largely made the Shabbos goy an anachronism, it was once a necessity. Illustrious personages such as Martin Scorcese, Mario Cuomo, Colin Powell, and a teenaged Elvis Presley once assisted Shabbat-observant neighbors in the US. My paternal grandmother (whose parents in America were no longer Shabbat-observant) reported back from a 1930 visit to family in Poland that the Polish Catholic Shabbos goy still faithfully executed her duties every Saturday morning. The following account by Joe Velarde, posted on Batya’s old blog, is a lovely tribute to the friendship that once existed in Brooklyn between Jewish and Christian neighbors. Enjoy.

Snow came early in the winter of 1933 when our extended Cuban family moved into the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn. I was ten years old. We were the first Spanish speakers to arrive, yet we fit more or less easily into that crowded, multicultural neighborhood. Soon we began learning a little Italian, a few Greek and Polish words, lots of Yiddish and some heavily accented English.

I first heard the expression Shabbes is falling when Mr. Rosenthal refused to open the door of his dry goods store on Bedford Avenue. My mother had sent me with a dime to buy a pair of black socks for my father. In those days, men wore mostly black and navy blue. Brown and gray were somehow special and cost more. Mr. Rosenthal stood inside the locked door, arms folded, glaring at me through the thick glass while a heavy snow and darkness began to fall on a Friday evening. “We’re closed, already”, Mr. Rosenthal had said, shaking his head, “can’t you see that Shabbes is falling? Don’t be a nudnik! Go home.” I could feel the cold wetness covering my head and thought that Shabbes was the Jewish word for snow.

My misperception of Shabbes didn’t last long, however, as the area’s dominant culture soon became apparent; Gentiles were the minority. From then on, as Shabbes fell with its immutable regularity and Jewish lore took over the life of the neighborhood, I came to realize that so many human activities, ordinarily mundane at any other time, ceased, and a palpable silence, a pleasant tranquillity, fell over all of us. It was then that a family with an urgent need would dispatch a youngster to “get the Spanish boy, and hurry.”

That was me. In time, I stopped being nameless and became Yussel, sometimes Yuss or Yusseleh. And so began my life as a Shabbes Goy, voluntarily doing chores for my neighbors on Friday nights and Saturdays: lighting stoves, running errands, getting a prescription for an old tante, stoking coal furnaces, putting lights on or out, clearing snow and ice from slippery sidewalks and stoops. Doing just about anything that was forbidden to the devout by their religious code.

Friday afternoons were special. I’d walk home from school assailed by the rich aroma emanating from Jewish kitchens preparing that evening’s special menu. By now, I had developed a list of steady “clients,” Jewish families who depended on me. Furnaces, in particular, demanded frequent tending during Brooklyn’s many freezing winters. I shudder remembering brutally cold winds blowing off the East River. Anticipation ran high as I thought of the warm home-baked treats I’d bring home that night after my Shabbes rounds were over. Thanks to me, my entire family had become Jewish pastry junkies. Moi? I’m still addicted to checkerboard cake, halvah and Egg Creams (made only with Fox’s Ubet chocolate syrup).

I remember as if it were yesterday how I discovered that Jews were the smartest people in the world. You see, in our Cuban household we all loved the ends of bread loaves and, to keep peace, my father always decided who would get them. One harsh winter night I was rewarded for my Shabbes ministrations with a loaf of warm challah (we pronounced it “holly”) and I knew I was witnessing genius! Who else could have invented a bread that had wonderfully crusted ends all over it — enough for everyone in a large family?

There was an “International” aspect to my teen years in Williamsburg. The Sternberg family had two sons who had fought with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in Spain. Whenever we kids could get their attention, they’d spellbind us with tales of hazardous adventures in the Spanish Civil War. These twenty-something war veterans also introduced us to a novel way of thinking, one that embraced such humane ideas as ‘From each according to his means and to each according to his needs’. In retrospect, this innocent exposure to a different philosophy was the starting point of a journey that would also incorporate the concept of Tzedakah in my personal guide to the

world.

In what historians would later call The Great Depression, a nickel was a lot of mazuma and its economic power could buy a brand new Spaldeen, our local name for the pink-colored rubber ball then produced by the Spalding Company. The famous Spaldeen was central to our endless street games: stickball and punchball or the simpler stoopball. One balmy summer evenings our youthful fantasies converted South Tenth Street into Ebbets Field with the Dodgers’ Dolph Camilli swinging a broom handle at a viciously curving Spaldeen thrown by the Giants’ great lefty, Carl Hubbell. We really thought it curved, I swear.

Our neighbors, magically transformed into spectators kibitzing from their brownstone stoops and windows, were treated to a unique version of major league baseball. My tenure as the resident Shabbes Goy came to an abrupt end after Pearl Harbor Day, December 7, 1941. I withdrew from Brooklyn College the following day and joined the U.S. Army. In June of 1944, the Army Air Corps shipped me home after flying sixty combat missions over Italy and the Balkans. I was overwhelmed to find that several of my Jewish friends and neighbors had set a place for me at their supper tables every Shabbes throughout my absence, including me in their prayers. What mitzvoth! My homecoming was highlighted by wonderful invitations to dinner. Can you imagine the effect after twenty-two months of Army field rations?

As my post-World War II life developed, the nature of the association I’d had with Jewish families during my formative years became clearer. I had learned the meaning of friendship, of loyalty, and of honor and respect. I discovered obedience without subservience. And caring about all living things had become as natural as breathing. The worth of a strong work ethic and of purposeful dedication was manifest. Love of learning blossomed and I began to set higher standards for my developing skills, and loftier goals for future activities and dreams. Mind, none of this was the result of any sort of formal instruction; my yeshiva had been the neighborhood. I learned these things, absorbed them actually says it better, by association and role modeling, by pursuing curious inquiry, and by what educators called “incidental learning” in the crucible that was pre-World War II Williamsburg. It seems many of life’s most elemental lessons are learned this way.

While my parents’ Cuban home sheltered me with warm, intimate affection and provided for my well-being and self esteem, the group of Jewish families I came to know and help in the Williamsburg of the 1930s was a surrogate tribe that abetted my teenage rite of passage to adulthood. One might even say we had experienced a special kind of Bar Mitzvah. I couldn’t explain then the concept of tikkun olam, but I realized as I matured how well I had been oriented by the Jewish experience to live it and to apply it. What a truly uplifting outlook on life it is to be genuinely motivated “to repair the world.”

In these twilight years when my good wife is occasionally told, “Your husband is a funny man,” I’m aware that my humor has its roots in the shticks of Second Avenue Yiddish Theater, entertainers at Catskill summer resorts, and their many imitators. And, when I argue issues of human or civil rights and am cautioned about showing too much zeal, I recall how chutzpah first flourished on Williamsburg sidewalks, competing for filberts (hazelnuts) with tough kids wearing payess and yarmulkes. Along the way I played chess and one-wall handball, learned to fence, listened to Rimsky-Korsakov, ate roasted chestnuts, read Maimonides and studied Saul Alinsky.

I am ever grateful for having had the opportunity to be a Shabbes Goy.

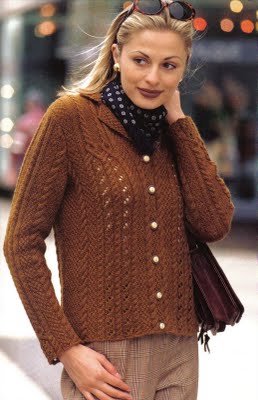

the hypnotic power of the computer screen. The fact is, I believe the computer is an addiction, not unlike caffeine or cigarettes. It troubles me to realize that I can sit down to it with a particular task to perform, get up two hours later and still not have done what I set out to do. I’ve checked email, written one or two, looked at my Facebook page, maybe left a comment or two on postings by friends, gone and looked at stuff from links, read a few blogs, the news, researched a few facts and checked out Cake Wrecks – and completely forgotten what I’d sat down to do in the first place. There goes two hours I could have spent knitting the fabulous Norah Gaughan sweater I’m working on (pictured at right), listening to a collection of CDs of the essays of Rabbi Y.Y. Rubinstein (a delightful Scots rabbi), doing small maintenance projects around the house, taking a walk or reading one of the half-dozen books sitting on my bedside table waiting to be read. Or working. (But let’s not take it too far.)

the hypnotic power of the computer screen. The fact is, I believe the computer is an addiction, not unlike caffeine or cigarettes. It troubles me to realize that I can sit down to it with a particular task to perform, get up two hours later and still not have done what I set out to do. I’ve checked email, written one or two, looked at my Facebook page, maybe left a comment or two on postings by friends, gone and looked at stuff from links, read a few blogs, the news, researched a few facts and checked out Cake Wrecks – and completely forgotten what I’d sat down to do in the first place. There goes two hours I could have spent knitting the fabulous Norah Gaughan sweater I’m working on (pictured at right), listening to a collection of CDs of the essays of Rabbi Y.Y. Rubinstein (a delightful Scots rabbi), doing small maintenance projects around the house, taking a walk or reading one of the half-dozen books sitting on my bedside table waiting to be read. Or working. (But let’s not take it too far.)